In this first chapter, we introduce assessment principles and strategies that inform the remainder of the resource package: the discussions of specific aspects of assessment practice presented in the following chapters, and the classroom examples included at the end of the package. We begin by discussing the change in focus from summative to formative assessment, and move from there to present five strategies that can guide the integration of assessment and learning activities in your classroom.

What is the Difference between Assessment for and Assessment of Learning?

Traditionally, assessment was seen to be either summative, identifying the result of learning at the end of a unit or course, or formative, providing learners with ongoing, often informal feedback throughout the learning process. However, while the two types of assessment might differ in timing and level of formality, many have argued that the two have often served the same function, that is, to determine if learning has occurred, providing “snapshots of where the [learners] have ‘got to’, rather than where they might be going next” (Torrance, 1993, p. 340). This type of assessment may have little impact on learning.

Assessment Practices that Promote Learning

What do we know about the assessment practices that best promote learning? In 1989, a group of U.K researchers came together to explore this question, and to strengthen the link between assessment practices and research evidence. This group later became known as the Assessment Reform Group, a loosely connected group of researchers who continued exploring assessment practices and advocating for reform through the 1990s and into the 2000s. Early in the group’s history, and in response to research suggesting that some assessment practices had more impact on learning than others, Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam conducted a review of over 250 quantitative studies of assessment, to identify practices that positively influenced learning (Black & Wiliam, 1998). They concluded that, while not all assessment practices had a positive effect on learning, those that did were formative in nature (Black & Wiliam, 1998). This seminal study introduced a key new understanding of assessment: innovative formative assessment can improve learning.

Black and Wiliam found that an increased emphasis on what they term assessment for learning contributes to positive learner achievement in the classroom. The primary purpose of assessment for learning is to provide feedback that will promote student learning, feedback that will help learners identify where they are and what they need to do next. This type of formative assessment is often informal and is integrated into all aspects of the teaching and learning process; it happens while learning is underway. Evidence is used to diagnose learner needs, plan next steps in instruction, and provide learners with feedback they can use to improve their performance. This can be contrasted with assessment of learning, which is the summative assessment that comes “after learning is supposed to have occurred to determine if it did” (Stiggins, Arter, Chappuis, & Chappuis, 2004, p. 31).

Members of the Assessment Reform Group went on to argue that all assessment should improve learning; even summative assessment should include formative elements (Harlen & Gardner, 2010, p. 19). An end of unit assessment task, for example, might provide information to be used for summative purposes (related to whether or not the learner met the criteria for task success), as well as information used for formative purposes: to analyze the gap between student learning and learning intents, to provide action-oriented feedback to learners, and to adjust ongoing teaching and learning activities.

Assessment for Learning and your Classroom

Your assessment context likely requires both assessment of learning and assessment for learning. You may be required to determine whether learners have met the expectations for a specific CLB benchmark level (assessments of learning), but you likely also give learners specific feedback that helps them to improve their language skills (assessment for learning), using both formal and informal assessments. This resource package includes examples of instructors using assessment for both purposes, with a focus on integrating assessment for learning into all assessment.

“Traditional approaches to instruction and assessment involve teaching some given material, and then, at the end of teaching, working out who has and hasn’t learned it – akin to a quality control approach in manufacturing. In contrast, assessment for learning involves adjusting teaching while the learning is still taking place – a quality assurance approach.”

(Leahy, Lyon, Thompson, & Wiliam, 2005, p. 19).

Can my Classroom Assessments Provide Dependable Information about Learner Progress?

In classroom-based assessment, assessment is carried out by the instructor, rather than by outside experts. Instructors tailor assessments to learner needs and goals and to the learning context; they do not rely on external, standardized tests. This classroom-based nature of assessment has led to lively discussion of the dependability of the information gained from assessments – after all, assessment information is only useful if it provides a reasonably accurate picture of where learners stand in comparison to learning intents.

Questions of accuracy have traditionally been framed in terms of validity, how well what is assessed corresponds with the learning outcomes being assessed, and reliability, the consistency of the results of assessment, if repeated.

Reconciling Validity and Reliability when Using Classroom-based Assessment

In many learning environments, the goals of validity and reliability compete. When reliability increases, it is frequently at the expense of validity, and when validity increases, reliability decreases. This inverse relationship is a factor in language classrooms adopting classroom-based assessment. In these classrooms, learning activities are tailored to the context, defined both by language standards frameworks like the CLB and by learner-identified needs. This context-dependent planning process strengthens assessment validity. Assessment activities and tools are similarly tailored, and as a result, can vary substantially from one classroom to another – again strengthening validity, but presenting challenges for traditional conceptions of reliability.

Additionally, in this sort of classroom-based assessment, skills and competencies are often revisited: they are practised and assessed in a variety of social situations and contexts. While this sort of layered and ongoing assessment is consistent with conceptions of validity, it does not fit well with traditional conceptions of reliable, replicable assessment.

Is reliability, then, achievable in the dynamic learning environments often seen in language classrooms? Assessment reformers would argue that acceptable reliability is possible, if we are willing to understand reliability to be established by frequent formal and informal assessment. In your classroom-based assessments, therefore, reliability can be supported by gathering assessment information about learner performance frequently, over time. In doing so, you build a large body of information about learners which over time facilitates dependable judgements about the learning that has or has not occurred in your classroom (Harlen, 2010; Black, Harrison, Hodgen, Marshall, & Serret, 2010, and 2011).

“Assessment procedures should include explicit processes to ensure that information is valid and is as reliable as necessary for its purpose.”

(Harlen, 2010, p. 19)

Treating Assessment as Approximation

In addition to these discussions of reliability, assessment reformers have questioned notions of assessment accuracy, challenging us to acknowledge that all assessment is approximate. Even the best assessment practices, they argue, can only provide a partial picture of a learner’s capability (Harlen, 2010, pp. 38-39). There are a number of reasons for this:

Assessment Day Conditions: On the day of an assessment, learners may perform better or worse than they might if given the same assessment another day; stress, fatigue, or a multitude of other influences can influence performance. Additionally, assessments are by necessity constrained by time and resources, and can only assess a sampling of learner performances.

The Nature of Language: In language classrooms, assessment is additionally complicated by the nature of language itself, which is much more than just a tool for communication. Language shapes how we look at the world, and how we interpret our experience. Language is who we are; it is what makes our experience accessible to us. Language use varies in response to intricate contextual factors related to personality, situation, and relationship. As a result, learning a language is an extremely complex, non-linear process, one that is not easily measured or quantified.

The CLB framework addresses competencies in four general areas (Interacting with Others, Following and Giving Instructions, Getting Things Done, and Sharing Information). These are competencies used in many different contexts, and directly observable. They are, however, only a sampling of a person’s ability at a particular benchmark level, the “tip of the iceberg” (Pawlikowska-Smith, 2000, p. 25). Indeed, some aspects of a learner’s language ability may not be described by the CLB framework, and thus may not be captured in assessment tasks.

Instructor Interpretation: Assessments of communicative language ability rely on interpretation, both of the CLB framework and of a learner’s performance. Instructors use professional judgement to determine whether a learner’s performance fits within a defined band of proficiency. There is bound to be a degree of variability.

Setting Conditions for Dependability

Despite these complexities, research suggests that your classroom-based assessment judgements can be dependable, when certain conditions are met (Harlen, 2004; Black et al., 2010, 2011). Two innovative studies by assessment reformers shaped this understanding: a review of 30 studies by Harlen (2004), and the KOSAP study, a longitudinal study with teacher educators / researchers (Black et al., 2010, 2011).

Both studies found that dependability increases when instructors work together to interpret assessment criteria. Both demonstrated the value of instructors getting together in moderation sessions (sometimes referred to as calibration sessions) to look at learner work together, developing a shared understanding of learning goals and related assessment criteria.

The studies also found that assessment judgements are made more dependable when instructors engage in the development of tasks, again fostering a deep understanding of learning goals and assessment criteria. In the Harlen study, teachers developed this understanding through the building of assessment tasks (2004, p. 267). In the KOSAP study, this understanding was fostered through the careful implementation of tasks, including introducing tasks and criteria to the class, choosing the degree of scaffolding, and implementing peer assessment (Black et al., 2010, 2011).

How can I Apply Assessment for Learning Principles in my Classroom?

While assessment reformers have made a compelling case for a close link between assessment for learning practices and improved learning, establishing these practices in the classroom requires a thoughtful, deliberate approach.

Five Assessment for Learning Strategies

Leahy, Lyon, Thompson, and Wiliam (2005) have identified five assessment for learning strategies which have been shown to lead to significant improvement in learning in a range of classrooms and learning contexts (Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshal, & Wiliam, 2003; Wiliam 2007).

Strategy 1: Clarify learning intents and criteria for success

Research suggests that learning is enhanced when the intentions or goals of learning and the assessment criteria are transparent to learners (Black & Wiliam, 1998, Leahy et al., 2005). In assessment for learning, instructors use information from a variety of sources to clarify learning intents. In programs that use the CLB this information includes

- program goals, determined by program context;

- the CLB framework;

- learner-identified needs, gathered from initial input and discussions with learners and from ongoing learner feedback during the learning and assessment process;

- assessment information gathered from classroom-based assessments integrated throughout the learning process

To facilitate learning, instructors share these learning intents with learners, along with criteria for success, and take specific steps to ensure that learners understand them in the context of their own learning, steps that go beyond simply posting the learning objective at the beginning of a task (Leahy et al., 2005).

“Low achievement is often the result of students failing to understand what teachers require of them.”

(Harlen, 2010, p. 19)

Strategy 2: Incorporate classroom activities that elicit evidence of learning

We also know that learning is enhanced when instructors include classroom activities that provide opportunities to engage individual learners, rather than opportunities to simply collect right and wrong answers. When assessing for learning, instructors listen interpretively, looking to understand what students do and do not know, and then use this understanding to adjust instruction (Leahy et al., 2005).

The authors suggest that instructors use strategies that encourage learner engagement, to elicit responses to questions from all learners, not only from those eager to offer a response. Instructors might use tools like learning journals or small group or pair response strategies to elicit evidence of learning from as many learners as is reasonably possible.

Strategy 3: Provide action-oriented feedback that moves learners forward

Research clearly shows that learning is enhanced when feedback, linked to criteria, is action-oriented and articulates the steps a learner needs to take to improve (Leahy et al., 2005). In assessment for learning, instructors increase the amount of descriptive feedback they are giving to learners, and limit the amount of evaluative feedback. In fact, instructors experimenting with comment-based feedback on tasks and assignments report a positive impact on learning (Leahy et al., 2005). While grades might motivate the most capable learners, they tend to discourage weaker students. Research also suggests that when grades are removed from an assessment, learners more readily focus on comments that can help them improve their work (Black & Wiliam, 1998).

Not all descriptive feedback is helpful, however. General comments like “good work” provide learners with no information on where their work sits in terms of goals, or how they might move forward. In assessment for learning, instructors try to provide feedback that is accurate, specific, and focused on how to build for success. Feedback includes three steps, originally suggested by Sadler (1989) and adopted by the Assessment Reform Group, and now widely used in assessment for learning resources:

- recognition of the desired goal,

- evidence of the present position, and

- knowledge about how to close the gap between the two.

“Feedback to any pupil should be about the particular qualities of his or her work, with advice on what he or she can do to improve…”

(Harlen, 2010, p. 19)

Strategy 4: Activate learners to become instructional resources for one another

Research suggests that learning is enhanced when learners support one another, including peer assessment (Leahy et al., 2005). Assessment for learning practices recognize that learners are often better able to notice things in their classmates’ work than in their own work. As learners use criteria and well-constructed assessment tools to review the work of classmates, they will strengthen their own understandings of the criteria underlying the task and tool.

Strategy 5: Activate learners to become owners of their own learning

Research also suggests that language learning is enhanced when learners use agreed-upon criteria to reflect on and assess their own learning (Leahy et al., 2005). In assessment for learning, instructors help learners to develop self-assessment skills; they also build opportunities for learner self-reflection into learning activities.

“Developing assessment for learning in one’s classroom involves altering the implicit contract between teacher and students by creating shared responsibility for learning.”

(Harlen, 2010, p. 19)

These five strategies guide the remainder of this resource package. As you read, you will see them interpreted in more detail in the chapters on specific assessment practices, and applied in the classroom examples.

Assessment and the CLB

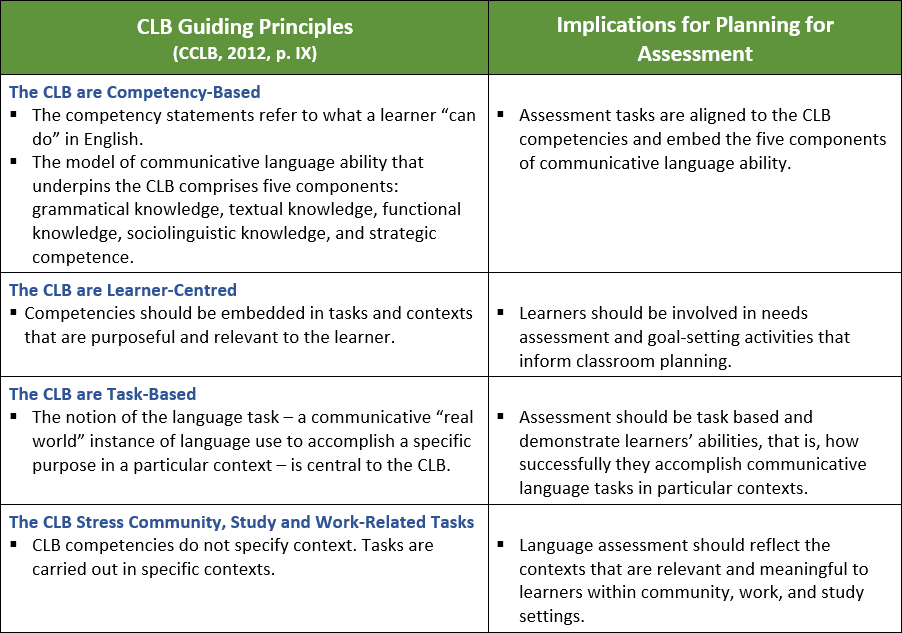

In programs where the CLB are applied, the four guiding principles of the CLB (CLB 2012, IX) also have implications for assessment. The four principles are summarized below, with the related implications for assessment.

Assessment and the CLB

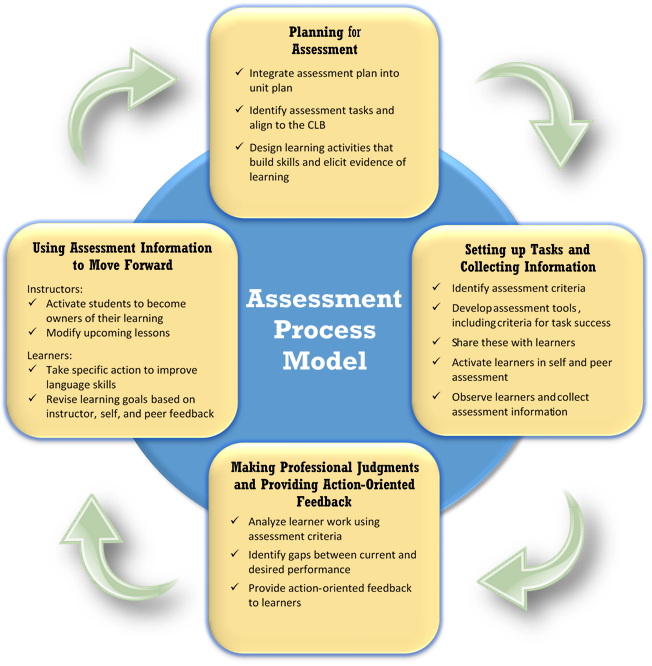

Assessment tasks do not exist in isolation, but fit with other learning and assessment tasks in a complex learning and assessment cycle, from planning, through application of assessment strategies, to further planning. You might find the model to the right a useful planning tool. In the ESL classroom examples at the end of this resource package, this model guides the components of the assessment process as they are worked out in practice.

References

Black, P., Harrison, C., Hodgen, J., Marshall, B., & Serret, N. (2010). Validity in teachers’ summative assessments. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 17(2), 217-34.

Black, P., Harrison, C., Hodgen, J., Marshall, B., & Serret, N. (2011). Can teachers’ summative assessments produce dependable results and also enhance classroom learning? Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 18(4), 451-469.

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2003). Assessment for learning: Putting it into practice. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. London, UK: King’s College London School of Education.

Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks (CCLB). (2012). Canadian Language Benchmarks: English as a second language for adults. Ottawa, ON: Author. Retrieved from http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/pdf/pub/language-benchmarks.pdf

Harlen, W. (2004). A systematic review of the evidence of reliability and validity of assessment by teachers used for summative purposes. In EPPI Centre, Research Evidence in Education Library. London, UK: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education. Retrieved from http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=6_1H03rsumM%3d&tabid=117&mid=923

Harlen, W. (2010). What is quality teacher assessment? In J. Gardner, W. Harlen, L. Hayward, & G. Stobart (Eds.), Developing teacher assessment (pp. 29-51). Berkshire, UK: Open University Press.

Harlen, W., & Gardner, J. (2010). Assessment to support learning. In J. Gardner, W. Harlen, L. Hayward, & G. Stobart (Eds.), Developing teacher assessment (pp. 15-28). Berkshire, UK: Open University Press.

Leahy, S., Lyon, C., Thompson, M., & Wiliam, D. (2005). Classroom assessment: Minute-by-minute and day-by-day. Educational Leadership, 63(3), 19-24.

Pawlikowska-Smith, G. (2000). Canadian Language Benchmarks 2000: Theoretical framework. Ottawa, ON: Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks.

Pettis, J.C. (2014). Portfolio-based language assessment (PBLA): Guide for teachers and programs. Ottawa, ON: Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks. Retrieved from http://new.language.ca/product/pbla-guide-pdf-e

Sadler. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18, 119-144.

Stiggins, R., Arter, J.A., Chappuis, J., & Chappuis, S. (2004). Classroom assessment for student learning: Doing it right – using it well. Portland, OR: Assessment Training Institute, Inc.

Torrance, H. (1993). Formative assessment: Some theoretical problems and empirical questions. Cambridge Journal of Education, 23, 333-343.

Wiliam, D., & Leahy, S.A. (2007). A theoretical foundation for formative assessment. In J. McMillan (Ed.), Formative classroom assessment: Theory into practice (pp. 29 – 42). New York: Teachers College Press.