Planning for assessment is an integral part of the instructional planning process, with assessment opportunities integrated both within and at the end of learning activities – assessment is not simply an “add on” at the end of the instructional cycle. This chapter does not explore the instructional planning process in detail, but instead supports the argument that effective assessment is deeply embedded in the instructional cycle, and must be as carefully planned for as other aspects of teaching.

The sections below present four assumptions underlying planning for assessment. As you read and reflect on your assessment practice, you will likely find many examples of how you are already embedding assessment in your instructional cycle, perhaps without thinking of it as such.

PRACTICE-BASED CONCERNS

“How do I plan for both assessment of and assessment for learning?

“How can I integrate assessment as a natural part of my classroom practice so it doesn’t feel like I’m just teaching and testing?”

Assumption #1: Planning for Assessment Considers the Purposes for Assessment

In classes that incorporate assessment for learning practice, all assessment is designed to enhance learning. However, the approach to assessment will differ, depending on whether the primary purpose is to provide assessment for learning feedback or whether the task will also be used to check what has been learned, to provide assessment of learning information. Determining the purpose(s) for the assessment will affect both the task design and set up (for example, how much support is provided), and the type of feedback that is provided.

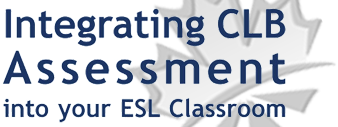

The table below is adapted from the typology of assessment possibilities developed by Chris Davison (Davison & Leung, 2009). The table describes three possibilities that move from very informal assessment for learning-while-teaching (on the left of the chart), to more formal assessment of learning (on the right).

Purposes for Assessment

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE CLB-ALIGNED CLASSROOM

The approach to assessment and strategies used will depend on the primary purpose for the assessment.

In-Class Contingent Assessment: Within classroom practice, instructors include contingent assessment on a variety of skill-building and skill-using activities on a daily basis, giving informal feedback, and adjusting instruction based on learner response. They incorporate a range of strategies:

- Feedback may be direct or may be indirect, through the use of open-ended questions to check for understanding, or learner self-reflection.

- Feedback may be to the individual learner or to the group. For example, during a partner role play, the instructor might comment to individual learners or pairs while moving around the room, or might circulate, observe learners, make notes, and then debrief key points with the full group.

- Feedback may be in the moment, or given after the task is completed. For example, in an ESL literacy class, an instructor might provide in-the-moment feedback by circulating while learners are filling out a form, or s/he might simply observe what the learners are doing, and address key issues after the task is completed or in an upcoming lesson.

- Assessment may include informal notes about learners’ spontaneous use of language outside structured learning tasks. For example, the instructor might note a learner’s appropriate use of apology for arriving to class late and record this as evidence of this competency, for use in decisions about learner achievement.

Planned Integrated Assessment: As part of classroom planning, instructors incorporate a range of CLB-aligned communicative language tasks. Some will be designed primarily to provide opportunity for growth and development as learners practice new skills and will include only assessment for learning feedback. These are sometimes referred to as “skill-using” tasks and may incorporate a variety of strategies:

- Tasks may include instructional support or scaffolding; for example, in a reading task, an instructor might begin by reviewing strategies learners can use to guess the meaning of new words in context. The level of support should be clearly indicated if tasks will be reviewed as part of the end of term evaluation process (e.g. in a portfolio).

- The feedback provided within these language learning tasks will typically be descriptive and non-evaluative, focusing on how the learners can improve based on their current performance.

- Feedback may include multiple sources (e.g. instructor, self, and/or peer assessment).

Formal Assessment: Other communicative tasks will be designed to give learners an opportunity to demonstrate what they can do related to benchmark expectations. Teachers will provide assessment of learning feedback, and tasks will include assessment criteria aligned to the CLB and an indication of what is required for success on the task. Learners will complete these tasks independently and the feedback to the learner will indicate whether or not they have met task expectations at a specific benchmark. In order to also provide assessment for learning support in the task, instructors will provide action-oriented feedback to learners to give them information they can use to improve their performance. For additional information related to providing feedback, see Chapter 7.

Planning for two Challenges of classroom-based Assessment

Considering the purpose(s) for the assessment can help address some of the common challenges of classroom-based assessment. The first challenge, often expressed by instructors beginning to implement classroom-based assessment, is that they feel like they are on a teaching and testing treadmill. If you feel like this, you may be jumping too quickly to assessment of learning tasks without sufficient time to focus on assessment for learning. Early in the term when learners are developing new skills, tasks that provide opportunity for practice and non-evaluative comments-only feedback are particularly important for growth and improvement. As you plan your assessment opportunities, you might emphasize assessment for learning feedback in the early stages of learning.

A second challenge relates to what has been called a false positive effect: learners are so well prepared and rehearsed for assessment tasks that they are able to complete an end of unit assessment task successfully, but unable to demonstrate the same abilities in a similar task several weeks later. A false positive can occur if the assessment task is too heavily supported. When learners complete an assessment of learning task, they should be completing it independently, without instructional support. A false positive can also occur if a task is used first as a skill-using activity, and later duplicated as an assessment task. As you prepare an assessment of learning task, keep in mind that learners should have practised the underlying skills for the task, but should not have rehearsed the exact task. For example, learners at CLB 3 might partner together to practise a speaking task in which they sit back to back and give short directions to a classmate using a map of the school neighborhood. They use self and peer assessment by comparing maps at the end of the activity. Later in the unit of study, they might use the same skills in a different context for an assessment of learning task in which they record their directions to a classmate using a simple map of the downtown area of the city, and receive instructor feedback. This change of task and context helps avoid false positives.

Additionally, over a course of study, instructors should plan for activities that allow learners to transfer their learning to new situations and to demonstrate some of the key competencies in new contexts, with diminishing amounts of support. This sort of planning will ensure that learners are able to transfer abilities to new contexts, again avoiding a false positive effect. For example, in a unit on renting an apartment, learners might complete a writing task in which they write a note of complaint to a landlord. In a later unit on shopping, the instructor might return to the skills of writing a short note to complain, with learners completing an assessment task in which they send a short e-mail to complain about an item they ordered through a website.

Assuming that you will be using evidence from classroom-based assessment to assign benchmarks, the follow questions can assist in planning.

Over the course of studies…

- Will the assessment tasks completed provide evidence of learner abilities across a range of competencies and contexts?

- Will learners have sufficient opportunity to develop and practise new skills and receive non-evaluative feedback in order to build for success?

- Will learners have opportunity to transfer their skills to increasingly distant contexts?

Consider the following example of assessment progression over a semester in a class working towards Writing Benchmark 4.

WRITING BENCHMARK 4

EARLY SEMESTER – ASSESSMENT FOR LEARNING TASK:

In a unit, Introducing Ourselves, learners are asked to write a paragraph to tell of their arrival in Canada for a classroom blog. One of the expectations for writing at CLB 4 is control of basic paragraph structure, but learners may not be familiar with the use of topic sentences. The instructor and class brainstorm possible topic sentences for their paragraphs and what information (supporting details) might be included. Criteria for the task are listed on the board and learners copy them onto their papers at the bottom of their paragraphs. Learners check each of the criteria they think they’ve met (learner self-assessment) before handing in their paragraphs. The instructor checks which criteria she thinks have been met, underlines selected errors for the learner to correct, and provides comments-only feedback to draw attention to one key thing each learner can do to improve.

WRITING BENCHMARK 4

MID SEMESTER – ASSESSMENT OF LEARNING TASK:

In a unit on local places of interest, learners complete a similar task as an assessment task at the end of the unit. They are asked to write an e-mail to a classmate telling about a visit they have made to a nearby landmark or place of interest. Learners complete the task independently. Before they begin writing, they are given the assessment tool – a rating scale with CLB-aligned criteria. The assessment tool indicates what constitutes task success at CLB 4. The instructor gives feedback related to task success using the rating scale, and supplements this with action-oriented feedback. Selected errors are circled on the email and learners can enlist help from a partner to correct their errors.

Assumption #2: Planning is based on Learner-Identified Needs

Consistent with one of the key principles of the CLB, planning for instruction and assessment is determined by learner-identified needs and goals related to work, study, and community contexts of relevance. Instructors incorporate ongoing needs assessment processes to ensure the appropriateness of the themes, topics, and social situations that are introduced in their classes.

The classroom examples at the end of this resource package illustrate planning and assessment based on learner needs.

Assumption #3: Real-World Tasks Form the Focus of Instruction and Assessment

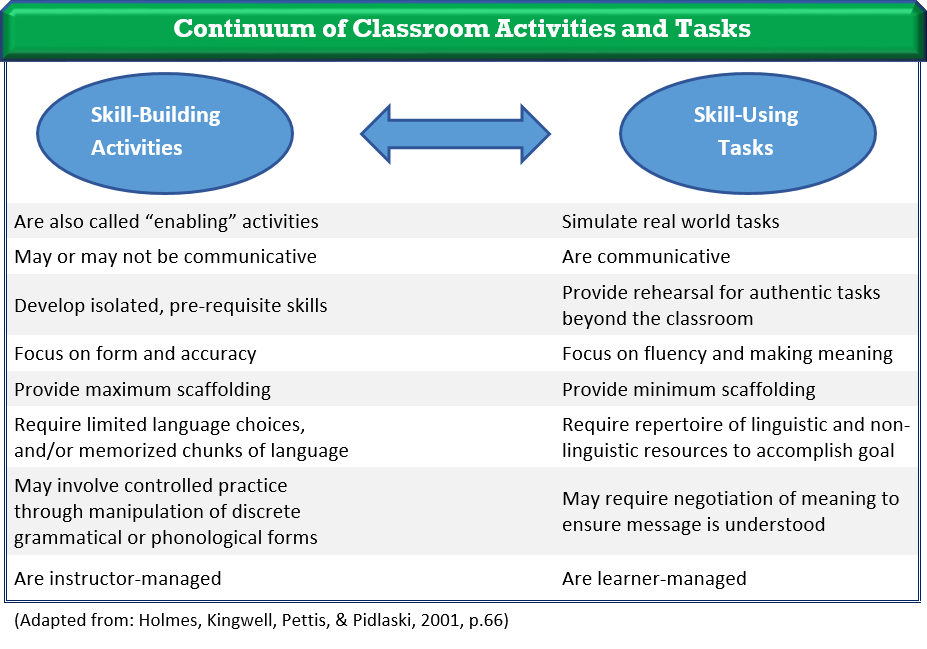

The CLB is a task-based framework focused on real-world tasks. The goal of instruction and assessment is to prepare learners to carry out language tasks successfully in their interactions beyond the classroom. To prepare learners for these real-world tasks, instructors will include a variety of language activities and tasks that range from skill-building activities to communicative skill-using tasks that simulate real-world tasks. The following continuum provides a comparison of skill-building and skill-using tasks, their uses and features.

Assumption #4: Unit Planning Helps to Focus Instruction and Assessment

Planning at the unit level, rather than identifying independent, “one-off” instructional and assessment tasks, helps us to plan with the end in mind – starting from the identification of learning outcomes (in this case the CLB), and using these outcomes to make decisions about methodology and content (Richards, 2013). Planning in this way has many advantages, leading to plans that

- reflect real-world language events (e.g. going to a walk-in clinic) which often require more than one skill area.

- provide multiple opportunities for learners to use and practise new language related to a topic (including, but not limited to, vocabulary, sociolinguistic knowledge, and language structures).

- ensure the assessment tasks are related to a range of classroom activities and become an integrated part of the instructional process.

- provide a blueprint of what needs to be taught and assessed.

- support instructional and assessment reliability through alignment to the CLB.

- ensure critical aspects of communication are not overlooked so learners can be successful.

If you are looking for approaches and templates for planning at the unit level, you’ll find many readily available. The classroom examples included in this resource package use a unit plan template based on the PBLA module plan template. It includes a number of elements critical to planning for instruction and assessment related to the CLB.

This unit template helps instructors plan for a set of interrelated real-world tasks related to a single topic or language event selected by the instructors in consultation with learners. When completed, the plan describes

- assessment tasks related to these real-world tasks in each of the four language skills (tasks which may be completed as assessment for learning tasks or more formal assessment of learning tasks).

- topic-related background information that is critical for success in the tasks.

- the competency(ies) addressed in the tasks.

- the grammatical, textual, functional sociolinguistic, and strategic elements that instructors will need to teach to prepare learners for these listening, speaking, reading and writing tasks.

Reflections on Your Practice

- Think about a unit of instruction you recently completed. Which of the competencies do learners need further work on? How might you address these competencies in a future unit?

- Think about a unit of instruction you are planning. What language tasks are you planning? Which will you use only for assessment for learning purposes? Which will you use for assessment of learning purposes?

References

Davison, C., & Leung, C. (2009). Current issues in English language teacher-based assessment. TESOL Quarterly, 43(3), 393-415.

Holmes, T., Kingwell, G., Pettis, J & Pidlaski, M., (2001) Canadian Language Benchmarks 2000: A guide to implementation. Ottawa, ON: Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks.

Richards, C., (2013). Curriculum approaches in language teaching: forward, central, and backward design. RELC Journal 44(1), 5-33.