Developing Speaking, Listening, Reading and Writing Skills in a Community-Based LINC Program

Kathy Chu: Classroom Instructor

Carly Whitley: Classroom Instructor

Sarah Schmuck: PBLA Regional Coach

Context

Type of classes: Community-based LINC program

CLB levels: 3 – 4

Kathy and Carly’s classes are both in community-based LINC programs. Kathy’s class is 8 hours per week, with semi-continuous intake. Carly’s class is 25 hours per week, with continuous intake. Both classes have a mix of language and educational backgrounds, genders, and ages. As noted above, both classes are designated as multi-level (CLB 3 and 4), and learners have a range of CLB levels within each of the four language skills.

The split classes (CLB 3 and 4) present both instructors with unique challenges related to supporting and assessing learners with a range of abilities. As they begin their semester, Sarah has been working on developing an efficient framework for multi-level assessment. After several conversations, this becomes an opportunity for Sarah, Kathy and Carly to work together to pilot Sarah’s proposed framework. To simplify the presentation here, their work is described as one classroom, with individual experiences providing the examples. In places where their experiences diverge, both perspectives are presented. In Kathy’s part-time class, the unit requires approximately four weeks of class time; in Carly’s, it requires approximately two weeks.

Planning for Assessment

At the start of classes, learners complete a needs assessment which asks questions about a variety of themes (and topics) related to community, work, and education. One of the topics learners identify as relevant is using a walk-in clinic, an experience they encounter frequently. Expressed interests include choosing a clinic, completing intake forms, and explaining the reason for their visit to the clinic.

Based on these interests, Carly and Kathy decide to pilot the unit, At the Walk-in Clinic. The listening and speaking real-world tasks focus on talking to the initial health care assessor (in most cases the nurse, but could be a doctor) to describe common ailments which don’t require urgent or emergency care. The writing goal is to complete an intake form with a medical history, including the reason for the visit. The reading goal is to find a clinic and look for specific information on their website. Because this unit is being used across two levels, Carly and Kathy ensure that the goals and assessment tasks are appropriate for both.

Writing the Unit Plan

The unit plan, which can be found at the end of the appendix or by following this link, includes the following elements:

- Real-world task goals in each skill area, as described above.

- Context/background information that is important for successful task completion.

- Competency areas and competency statements for each task.

- Language focus and learning strategies that are relevant for each task. (The Sample Indicators of Ability, Profiles of Ability and the Knowledge and Strategies for the Stage assist in identifying these items).

- Assessment tasks, which are as close to the “real world” as possible within the confines of the classroom.

Planning for Activities and Assessments

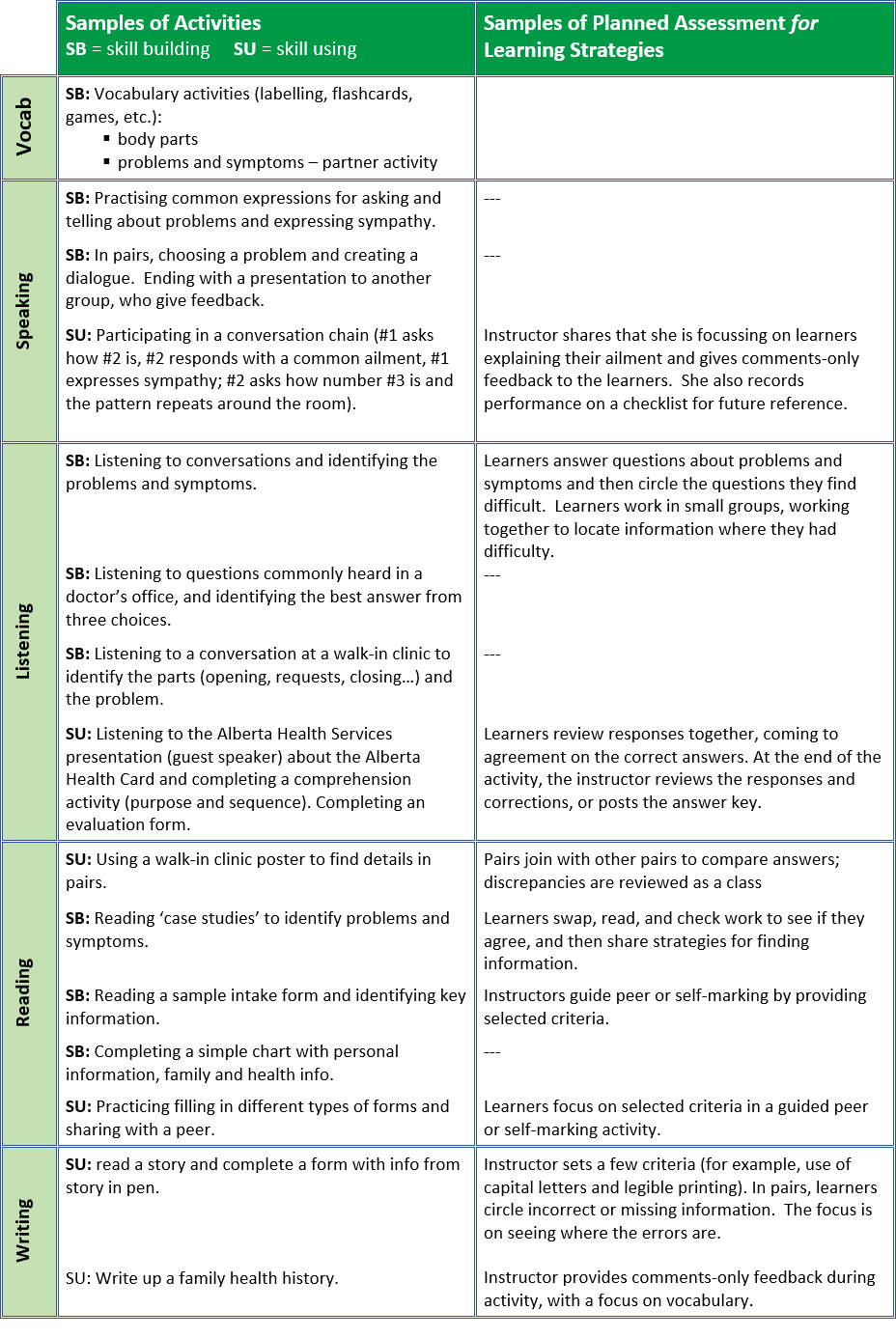

Kathy and Carly identify activities to build learners’ language skills and elicit evidence of learning. While planning, Kathy and Carly consider the assessment strategies they will use during the unit. They want to give feedback that will support learner growth, and they also want to keep track of learner progress. They plan to base their assessment for learning on oral feedback given during the various activities and tasks.

They also plan to promote self-assessment and to use peers as instructional resources. For example, as a general strategy in skill-building activities, they plan to support learners in checking their own work, and to encourage peer support by asking learners to consult with a peer once they have checked their own work. Learners will be asked to draw a line through their errors and write the correction above, or to complete work in one colour pen and mark with another. They also plan to incorporate directed peer feedback on certain activities.

Additionally, both instructors plan to use observational checklists and anecdotal records to keep track of their learners’ progress, as they do in other classes. Carly keeps her anecdotal notes in a notebook. When her volunteer is in the class, she uses the opportunity to review these notes and chat with learners about assessments or skill-using activities. In a full-time class like this, she finds it possible to provide small amounts of one-on-one support every week.

A sampling of planned activities and assessments are provided in the table below, with SB indicating skill-building activities (where learners develop the components of new skills), and SU indicating skill-using activities (where learners integrate these components to accomplish a communicative task). As you read through the table, you will see that several of the activities and assessments are designed to build the confidence and independence learners need to move towards their language learning goals.

Planning for Activities & Assessment: Samples of Activities

The sections below describe the assessment cycle applied to Carly and Kathy’s end of unit assessment tasks. As you read through, you will notice that while the tasks are designed with an assessment of learning purpose, they are carefully constructed to include multiple opportunities for assessment for learning.

For ease of reading, we have separated the discussion by language skills: 1) speaking/listening, 2) reading, and 3) writing.

The Assessment Cycle: Speaking and Listening

Listening and speaking are often assessed separately, but this unit provides a unique opportunity to look at a case where they were assessed together.

Designing the Listening and Speaking Assessment Task

Kathy and Carly use a one-on-one role play for this assessment, with the instructor acting as the clinic intake professional. (One-on-one assessments are time consuming so are used sparingly.) They video or audio record the role plays to allow assessment after the performances, and to give learners an opportunity for self-assessment and learning reflection.

Kathy and Carly start by designing a listening task that works for both levels. They develop a set of questions (one half of the dialogue) that would follow the standard sequencing of questions used in a clinic intake situation. They review the language focus as defined in the unit plan (and originally selected based on the CLB), to ensure they are addressing all of the assessment criteria that they have identified as important at CLB 3 and CLB 4.

They also consider Skehan’s (1998) framework for task difficulty, and decide to adjust the task in the following ways:

Linguistically: increasing the vocabulary load for CLB4,

Cognitively: making the follow-up questions unpredictable for CLB 4,

Communicatively: including more questions for CLB 4.

Finally they identify the criteria for task success for each level.

Designing the Listening and Speaking Tool

For the speaking task, Carly and Kathy develop the assessment tool shown below, one tool to be used with both groups. They decide to use a checklist based on two categories: meets expectations or needs work. To identify the assessment criteria they ask themselves: “What skills are important to accomplish this task?” They choose four key criteria, making sure that they are addressing more than grammatical knowledge. They return to the CLB document and to the unit plan to remind themselves of the indicators of ability and features of communication that distinguish CLB 3 from CLB 4.

Listening and Speaking Assessment Tool

On the assessment tool, Kathy and Carly articulate the criteria and the difference in expectations. As well, they link the criteria to the questions on the listening task to ensure that there is a match between the answers and the speaking assessment criteria. Finally, they identify the criteria for task success for each level, described at the base of the assessment tool.

Setting up the Listening and Speaking Task and Collecting Information

In class the day before the role play, Carly and Kathy explain the task set up and recording process, and review the speaking assessment tool and the criteria for task success for both speaking and listening. Kathy and Carly reassure learners that the assessment task is based on the skills they have been developing and practising in class. They do not provide the illness cues in advance, to discourage learners from preparing scripts. As well, they review some tips on how to prepare for the task.

On the day of the assessment, individual learners are given illness cue cards and a few minutes to think before they “meet with the doctor”; they aren’t allowed to use dictionaries or chat with others. They then “enter the clinic” and interact with the instructor. Because it is difficult to assess listening and speaking at the same time, Kathy and Carly assess listening comprehension during the interview by checking off whether the question has been answered, based on the content of the responses and not on the quality of speech. Kathy video records the interviews; Carly uses a USB audio recorder.

When finished with the interviews, Kathy reviews the videos and completes her speaking assessments. Carly reviews the audio recording with each learner immediately after the interview. During this time, she completes her speaking assessment and provides action-oriented comments. While she does this, the learner fills out a self-assessment.

With learners’ permission, Carly selects a few recordings to listen to with the whole class; Kathy does the same with the video recordings. The learners are excited about watching their peers and themselves, so several volunteer to share their performance.

Making Professional Judgements and Giving Feedback on the Listening and Speaking Task

When Carly and Kathy return their completed assessments to learners, they debrief the activity, giving learners a chance to talk about the experience of being interviewed and recorded. They further prepare the group to watch / listen to several recordings by explaining the two purposes of doing so:

- Self-reflection: to review individual performance based on the criteria for task success and to compare what they observe with the instructor’s comments.

- Group discussion: to focus on specific criteria and look for the differences between CLB 3 and CLB 4.

Carly and Kathy establish guidelines for learners commenting on each other’s work: they ask that comments be based on the criteria, with one positive comment made before any (polite) critique is provided.

Learners are enthusiastic about reviewing the interviews, and make several relevant comments about the differences between CLB 3 and 4, including

“They use complete sentences.”

“They speak in longer sentences and use lots of words and expressions from the lessons.”

“They don’t pause and hesitate too much.”

“You can understand them.”

Learners describe the activity as very helpful – because they were able to see the difference between a CLB 3 and CLB 4 performance. They also indicate that the language-focused conversation is both motivating and informative. When finished, they file their results in their portfolios, and during computer lab time, store the recordings in their electronic folders.

This video/audio review activity adds effective assessment for learning opportunities to this speaking and listening task, designed with an assessment of learning purpose in mind.

Using Assessment Information to Move Forward in Speaking and Listening

For Kathy, this unit is early in the term, so she plans to revisit the competency areas in other units based on the needs assessment. In a shopping unit she plans to review asking for help and making requests for information (Getting Things Done). In an upcoming unit on issuing invitations, she plans to revisit the competency area Interacting with Others (opening and closing conversations, asking and responding to personal questions). For Carly, these competency areas are revisited in employment, goals/resolutions and volunteering units. In one recent term, Kathy also took advantage of a real-world opportunity to complete a mini unit on expressing sympathy when a classmate had to return to her home country due the death of her father. The class role-played expressing sympathy for bad news and worked on reading and writing sympathy cards.

The Assessment Cycle: Reading

Kathy and Carly’s reading assessment task is tied to the unit real-world task goal of finding information about a walk-in clinic.

Designing the Reading Task

In designing the reading task and text, Kathy and Carly’s goal is to use one text and create one task. Their first step is to find the text. They select a website for a local walk-in clinic and check the webpage against Some Features of Communication. The webpage is text heavy so Carly and Kathy modify it by deleting several sections to reduce the content. They do not rewrite the text, and keep the visuals to support the text. The text is appropriate for CLB 4, the higher level they are assessing. An adapted version of their text is shown below, and at this link.

Reading Text

After setting the text, they create the task. Again, they ask themselves: “What skills are important to accomplish this task?” This particular task focuses on looking for key information (literal), but as is often the case, readers will also go to a page like this to make decisions/choices, so Kathy and Carly also include evaluative questions requiring a choice or decision. To modify the task, they consult Some Features of Communication in the CLB document. They also consider Skehan’s (1998) framework for task difficulty and decide to adjust the task in the following ways:

Linguistically: no modifications

Cognitively: providing questions that require less cognitive processing for CLB 3

Communicatively: reducing the number of questions and simplifying the types of responses for CLB 3.

Finally they decide on the criteria for task success.

The task and the assessment tool are integrated in this reading assessment. As you can see in the document below, the criteria for task success is included at the bottom of the task.

Reading Task and Tool

Setting up the Reading Task and Collecting Information

On the day of the assessment, using a visual on the screen, Kathy and Carly explain the task and carefully review the instructions and the criteria for task success. CLB 4 learners are told to complete Parts 1-3. CLB 3 learners are only required to complete Parts 1 & 2, but are invited to complete Part 3 as well, if they wish. A few learners decide to do this. Typically, when all learners in the class undertake the same task, the learners at higher CLB levels finish sooner than those who are working at lower CLB levels, a reality that can cause stress in the class. On this task, however, learners finish their respective parts at roughly the same time.

Making Professional Judgements and Giving Feedback on the Reading Task

After marking responses, Kathy and Carly return them to learners; you can see how they assessed the reading task on the completed samples for Learner 1 and Learner 2. They go over the answers with the whole class rather than in small groups. They have learners work together to identify how and where they found the answers, sharing reading strategies with others in the class.

In Carly’s class, the CLB 3 learners who attempt the CLB 4 level questions are successful. Carly is not surprised because they are advanced in their CLB level; she is pleased that the classroom work has given them the confidence to push themselves. The CLB 3 learners who did not complete the full activity indicated that they chose not to because they prefer to finish when everyone else does.

Using Assessment Information to Move Forward in Reading

Reading strategies such as skimming, scanning and using textual clues are incorporated into all of Carly’s and Kathy’s units. Where applicable, they include activities that require learners to use information they have gathered to make decisions or give an opinion. Additionally, because reading the webpage created awareness of how format can support reading comprehension, both instructors continue to emphasize this point in units on transportation and community, for example, while reading a transit schedule or a community center program guide.

The Assessment Cycle: Writing

As with the other assessment tasks, the writing assessment task is based on a walk-in clinic scenario.

Designing the Writing Task

The writing task requires filling out a medical form, so Carly and Kathy amalgamate several forms to create a 20-item medical form. They modify the task for CLB 3 learners by decreasing the length of the form to 16 items. They check Some Features of Communication in the CLB document ensure that the language of the task is level-appropriate. The form is reprinted below.

Writing Task

In the assessment tool (presented below), they use a checklist, with two categories: meets, or not yet. They select assessment criteria based on the question: “What skills are important to accomplish this task?” Again, they return to the CLB document and to the unit plan to remind themselves of the indicators of ability that distinguish CLB 3 from CLB 4, to ensure expectations are level appropriate. They identify four analytic criteria (accuracy, legibility, conventions for phone numbers and other information, and for CLB 4, correct spelling of basic key words).

The criteria for task success for both levels are included on the tool, as are clear directions for completion: CLB 3 learners complete Parts A-C; CLB 4 learners complete Parts A-D. Part D asks questions about personal health, an important part of many health forms. Kathy and Carly know that some of their learners have no health issues so will discuss using none or N/A. They include a section to record their feedback.

Writing Task Assessment Tool

Setting up the Writing Task and Collecting Information

On the day of the assessment, Kathy and Carly review the directions for completion, encouraging CLB 3 learners to try the CLB 4 part if they want. As well, they present the assessment tool and review the assessment criteria and the criteria for task success. Before starting, they remind learners to take their time, be accurate, use a pen, and check their work before handing it in.

As with the reading task, the two CLB levels finish at roughly the same time. In Carly’s class, despite being encouraged to do so, none of the CLB 3 learners attempt the CLB 4 component. The instructors hand out the assessment tool, and ask learners to indicate their evaluation of their work by placing an initial in one of the two categories beside each of the criteria.

Making Professional Judgements and Providing Feedback on the Writing Task

Before returning the learners’ work, Kathy uses learner input to complete the form with her personal information on an overhead, making intentional errors for learners to correct. In addition to content, learners point out where she needs to pay attention to spelling, punctuation, and other items related to accuracy. Kathy then hands back the medical forms, and learners evaluate their work against the exemplar on the overhead.

The returned forms and assessment tools do not include corrections of learners’ work, but instead provide feedback which identifies where learners need to make corrections. Their feedback centers on the task assessment criteria. You can see some of these comments on the completed samples for Learner 1 and Learner 2. In class, both instructors provide time for learners to review their work and to apply the feedback by making the necessary corrections. Carly encourages learners to go back to previous similar writing tasks (forms) to reflect on their progress, to see where they have improved and where they are making consistent errors. While learners are working on corrections, Carly and Kathy circulate and support learners. When learners finish, they show their revised work to Kathy and Carly, who keep track on a checklist – noting those who are still having difficulties.

Using Assessment Information to Move Forward in Writing

In Carly’s and Kathy’s class, learners also complete forms and applications during units on employment and volunteering. In Kathy’s class, in a real life situation later in the term, learners fill in a registration form for a Newcomers Fair.

Kathy and Carly: Reflections on Taking their Practice Forward

Kathy and Carly were enthusiastic about piloting the multi-level assessment unit and the impact it has had on learners and on their own practice.

Kathy’s Comments:

When teaching this unit, I found it rewarding to be able to assess the learners at the level that best reflects where they are working. It can be frustrating to make an assessment that will cause some of learners to become discouraged because it is too hard, or others to become bored because it is not challenging enough. On the speaking task, distinguishing a CLB 3 from a CLB 4 was not only rewarding for me as an instructor, but also valuable for the learners. For the first time, I felt like they were able to clearly identify the differences between CLB 3 and 4. Video recording the role plays was a new experience for me, and when we watched them together, the learners immediately identified what was successful and what could be improved. After a couple of videos, I referred to their feedback forms to show how a learner working at CLB 3 mostly uses words and short sentences, while a learner working at CLB 4 uses longer connected sentences. After watching two or three more videos, they were easily able to point out what a CLB 3 was, and what a CLB 4 was, and could recognize it in their own video as well.

Without prompting, learners said how much they enjoyed the role play, how much they had learned, how helpful it was in their own lives, and that it was new for them. The reactions of the learners caused me to feel better as an instructor: no one was isolated or left out. I found myself very aware of the CLB document. It provides a lot of support for multi-level assessment, and this support helped me articulate the differences between the two levels.

I learned strategies for identifying key differences between benchmarks and how I might incorporate those differences into my assessment task design and task tool. Going forward, I will modify tasks on a more regular basis to provide a more accurate picture of what the learner can do within the benchmark they are working in and toward. In turn, that will help me make a better evaluation of their progress and level when they have enough evidence.

Carly’s Comments:

This unit was very successful because the learners felt a sense of achievement. Most of all, the learners could see the differences in what was expected for each level. Nobody felt left out and everyone felt some sense of learning.

In class, the same skill-building and skill-using activities/tasks were used with both levels. It was only on the assessment task that I modified what the lower level was expected to do. This promoted a sense of ownership of their learning as they could choose which level to complete. I encourage learners to try for the higher level and see what happens (although not everyone does), as another way of showing learners how they can control their own education and have their learning matter for use in the real world.

I learned how important it is to anchor my tasks and tools in the CLB document. With the support of the CLB document, it is easy to distinguish the minute differences between varying levels. After implementing this project in my class, I see how important differentiated assessment is in split levels. An instructor usually teaches to the higher, while the lower level is always playing catch-up. I now ensure that I am making it possible for both levels to succeed within their own abilities.

I have also started to modify other tasks and tools that I recycle from past units. The listening and speaking tool has become a part of most of my units. I have only had to change the questions so that they pertain to my topic of choice. I’ve used it in my employment, volunteering, and goals/resolutions units. Spin-offs of the tasks in the Walk-in Clinic unit have regularly come up in subsequent lessons: filling in application forms/employment, finding details in a web page/transit schedules, etc. I have found that learners excel because they have recycled the skills in different contexts. In addition, they see that the skills they are learning are applicable to a variety of situations.